What’s It About

Maia is the only son of the fourth wife of the Emperor of the Elflands. Following his mother’s premature death, the Emperor (not the most loving of fathers) banishes him to a household in the middle of nowhere to be mentored by an abusive cousin. And then one morning Maia wakes up to the news that his father and brothers are dead – killed in an airship crash – and that he is now the Emperor of the Elflands.

Representative Paragraph

I’m not really doing this scene justice by cherry-picking this little moment, but Maia’s reaction to the model bridge is my favourite bit of the novel:

Maia barely heard the ensuing discussion, vehement though it was. He was too entranced by the model. As he looked closer, he could see that there were tiny people among the houses: a woman hanging laundry, a man weeding his vegetable garden, two children playing hider and seeker. There was even a tiny tabby cat sunning itself in a window. On the road toward the bridge, a wagon pulled by two dappled horses had stopped while the driver rummaged for something beneath his seat. Looking to the other side of the river, Maia suddenly spotted the cowherd among the cows, and he barely restrained a crow of delight. The cowherd, goblin-dark, was sitting cross-legged beneath the only tree in the pasture and playing a flute, so carefully rendered that each fingerhole was distinctly visible.

Should I Read It?

OMG YES!

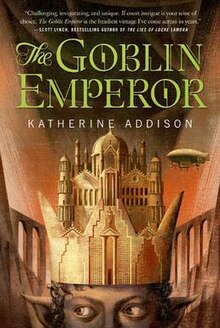

I remarked on the Coode Street podcast that The Goblin Emperor had a Downton Abbey vibe. But what I should have said is that I haven’t been this emotionally engaged with a fantasy novel since Guy Gavriel Kay’s Tigana. And whether that statement resonates with you or not, this is a book that earns every tear and laugh it elicits from the reader.

Commentary

While I appreciated the way Addison cleverly interweaves discussions about class, gender, race and sexuality into a novel that deals with power and privilege, there are three aspects of The Goblin Emperor that, for me, had the strongest impact.

First off, I loved that this was a book about a boy and his deep love for his mother. It’s clear that the premature death of the Empress left a psychic scar on Maia:

If he could simply have lain down and died of grief, he would have. His mother had been the world to him, and although she had done her best to prepare him, he had been too young fully to understand what death meant—until she was gone, and the great, raw, gaping hole in his heart could not be filled or patched or mended. He looked for her everywhere, even after he had been shown her body—looked and looked and she could not be found.

Unable to deal with his grief as a boy, Maia continues to struggle with that pain ten years later. But while he can no longer afford the tears, now that he is Emperor, he will do everything in his power to redeem her memory in the eyes of those who dismissed her as a “goblin” and not worthy of marrying his father (the previous Emperor). Obviously, class and gender plays a pivotal role in how Maia’s mother was treated by her husband and his cohorts. But what deeply affected me was how Maia’s remembrances of his mother – burdened with sadness and anger at how she was treated – very much highlights the sort of person she was, that is a woman deeply appreciative of her culture, which she tries to pass onto Maia, and a mother who experienced a deep bond with her son, unblemished by cynicism, court politics and the Machiavellian plans of others.

I also enjoyed Addison’s exploration of friendship. Again, class and power play a major role in this aspect of the novel. Specifically, Addison questions whether people of privilege can ever truly have long-term relationships with those who are on a lower rung of society’s ladder. In the case of Maia, he finds himself bonding with his bodyguards and his secretary and yet is deeply upset at how his friendship isn’t so much rejected as reluctantly set aside. As his bodyguards explain, their job is to protect him until death (literally) and any sort of true friendship will get in the way of that duty. In the end, Maia comes to the following realisation while discussing the issue with his bodyguards:

Almost breathless with his own ferocity, Maia said, “It is true that we cannot be friends in the commonly understood sense, but I have never in all my life had such a friend, and I do not think I ever will. I am the emperor. I can’t. But that doesn’t mean I can’t have friends at all, just that they can’t be that sort of friend. I believe that the Adremaza meant his advice for the best, but he was cruelly wrong. I do not ask, or expect, you to be friends with me as you are friends with other mazei, or other soldiers in the Untheileneise Guard. But it … it’s silly to deny that we hold each other in affection.” He stopped, swallowed hard. “If, of course, you do.”

“Of course we do,” Beshelar said, using the plural rather than the formal.

“For my part,” Cala said, “I have never been able to stop thinking of you as—you are right, not as a friend, exactly, but … I would die for you, Serenity, and not only because I swore an oath.”

“As would I,” said Beshelar.

Maia blinked hard and said, “Then we will be a different sort of friends. The sort we CAN be. All right?”

And finally there’s the fact that Maia gets to commission the building of a bridge. A good chunk of the plot is devoted to Maia’s desire to do something constructive with his power. And that moment when he sees that model bridge, and all those model people, and the model cow and the model kids (quoted above)… well, it gives me goosebumps just describing it. Yes, the notion of erecting a bridge might come across as an obvious metaphor – because isn’t Maia himself a bridge between the Goblin and Elf Empires, being a child of mixed blood? – but in actuality it’s a demonstration of a ruler who genuinely wants to improve the conditions for all his people and not just the select few.

The book does have its flaws. While bad things happen to Maia during his rule, they’re all resolved quickly and with only a modicum of fuss. And in the great scheme of thing Maia sacrifices little to get what he wants (though I’m sure he would disagree with me). Also his constant angst and doubt at his own abilities becomes tiring after a while. I understand why it’s there, but there comes a point when you want to grab the young Emperor by the scruff and bellow at him that he’s already proven his competence that he needs to stop with the self-deprecation and the false modesty. That he needs to get a backbone.

But these issues are minor. Overall this is an emotional engaging and beautifully written novel that, unlike so much fantasy around it, is entirely self-contained. What’s more remarkable is that somehow, in among all the recent crap, The Goblin Emperor was nominated for a Hugo award. And what that shows is that great fiction, fiction that speak to us intellectually and emotionally, will rise above the agendas and conspiracy fueled paranoia of Sad and Rabid Puppies.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks