If you filed off some of the dates in The Genocides – such as the fact that the Plants started appearing in 1972 and that the cities had fallen by 1979 – you wouldn’t know that this novel had been written over five decades ago.

If you filed off some of the dates in The Genocides – such as the fact that the Plants started appearing in 1972 and that the cities had fallen by 1979 – you wouldn’t know that this novel had been written over five decades ago.

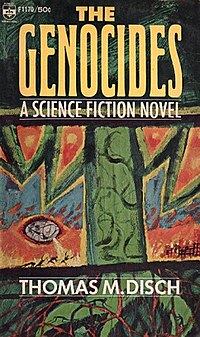

The Genocides details the invasion of Earth by Plants. Millions of these trees start growing across the world, sucking up nutrients, killing off the wildlife and basically turning Earth into a feeding ground. Within seven years, the cities are nothing more than ash and cinder and humanity is on the run, desperate to survive against a force that keeps on sprouting and sprouting and sprouting. The story takes place in Northern Minnesota where a small community, led by the bible thumping Mr Anderson, is trying to survive the coming end of days. I’m not gonna tell you what happens next. Because you’re all going to be smart and read it instead.

I don’t go for post-apocalyptic novels generally. I haven’t read Ballard’s Hothouse or The Death of Grass by John Christopher, or for that matter the Day of the Triffids. As a whole, these books about small packs of human trying to survive and stave off the inevitable don’t really float my boat. And yet The Genocides did. As much as this book follows a number of the conventions set by post-apocalyptic novels, there’s something about the sheer, unflinching grimness of the book that kept me reading. There’s a truth to the way the characters are depicted, especially in how they react to what’s going on. And their descent, both literal (read the novel) and figuratively, makes for disturbing reading.

It’s no surprise then that Algys Budrys gave the book a good kicking when it came out in 1965. From the little I’ve read, Budrys saw the novel as a poor copy of the Ballardian model (which came to be known by others as the New Wave), and called the The Genocides both nihilistic (which it isn’t, it’s just not very optiistc) and derivative (which it is, to a degree, but only in the sense that it’s playing in the same sandpit as Ballard). (As a side note, Disch never took well to this review or Budrys as a person as indicated by this LJ post commenting on Budrys’ death). Personally, I think Budrys was wrong. The Genocides, with its matter of fact writing style, is before it’s time rather than derivative of someone else’s work. It’s a remarkable novel that tells a very human story about survival, faith and of barbarism.

Hi Ian, It’s hardly surprising you haven’t read Ballard’s “Hothouse”, neither has anybody else. There is no such book. Brian Aldiss wrote a far-future novel called “Hothouse” in the Stapledonian mode. Most definitely not post-apocalyptic. You may have been thinking “Drought” by J G Ballard. Post-apocalypse is and has been a well-established literary tradition in SF. Tom Disch was engaged in doing his own take on the less than cosy catastrophe. Good to see someone trying to keep his memory alive. A wonderful stylist with a dark mordant wit. Pity his work has been eclipsed and is often overlooked. There’s much gold in his early novels and short stories. I remember George Turner being eager to meet Tom Disch, calling him the only writer worth talking to, at Seacon in 1979. I shall be interested in seeing more of your Disch reviews. best,Jeff

Thanks for the correction. I should have checked that when revising the review. And yes, his work is overlooked and I liked to play a small role in rectifying that.